For this edition of More Than Chairs, we interviewed Ann Beha and Amber Freedman from Ann Beha Architects. We discussed how they entered the design world, their interests in restoration design, and more.

Ann, how did you get yourself into the design world? Will you share a little bit about your history, and the firm’s history.

Ann Beha: Well, you know, these things are more about luck than being smart. I was in college at Wellesley and it had a cross-registration program at MIT. I was really interested in history, and I started to take courses on urban history and city history. You know, buildings really make the city. So, I got really interested in that and started to pursue it. One of the faculty members [at MIT] said: “You know, you’re really interested in buildings and how they come together, the design, and how these cities evolve. Why don’t you try the design studio?” Because they [MIT] had design studios, which they didn’t have at Wellesley. I started as an undergraduate to take some of the design studio courses. That’s really how it happened. Teachers are amazing. They make the difference.

Then I went to the design studio, and they weren’t so happy to have me. A lot of people there had taken design all their lives and they were really good artists. That wasn’t the side of the brain that I had really been exercising, so it was a big transition. It was really intriguing, partly because it was so hard.

When did you decide to go out on your own?

Ann: The economy when I got out of MIT was terrible. Nobody was hiring anyone. It was 1975, and there was a recession. I went to work in academia for a couple of years at MIT as an Assistant to the Head of the Department of Architecture. That wasn’t a design position, but it was more time with mature and accomplished designers who were faculty. I learned a lot from being around them. It exposed me to the actual dynamics of making a place work with a lot of people. They had people who were different and had different opinions all work towards one purpose. They have a very creative environment at MIT. People don’t always agree, but they move in a creative way around the differences between them. That’s a lot like running an architecture firm. People don’t agree, but they move in a creative way towards a shared outcome.

When I worked at MIT one of my focuses was building technology and preservation which includes understanding materiality. I’d done a lot of work in that. I met some people who were working more in preservation, and I started to spend more time with them. That got me a consulting job working in preservation. So, my first years were kind of building a preservation practice. From there I started to think more about design and started a practice that was more design-orientated. But preservation was still new and there weren’t that many people doing it, so it was easy to get on panels and start talking about it. I did a lot of volunteer community work. I built a lot of relationships with different groups in Boston. It just took off from there.

When did preservation become important to you?

Ann: Well, really through MIT and materials technology. MIT has a very strong technological bent and there was a lot of focus on material science and engineering as part of the design initiative. I mean, you could assume that right? It’s what they’re known for. So that was a very interesting part because we were looking a lot at archaic materials, you know, nineteenth-century brick, sandstone, different types of igneous rocks, metamorphic rocks, and how those were used in material science. And that’s just part of the building technology curriculum at MIT. The key to preservation is understanding materials and how they can be treated and what their capacity is. You know, building codes at that time were discriminating, if you will, against renovation and rehabilitation because all the codes were written for new construction. So, I got a research gig for the National Building Center in Washington through MIT studying building codes for historic buildings and how building codes should be adapted to become more performance-based and less prescriptive. That was another thing I was doing while actually waiting to practice architecture. I was waiting for the economy to need me.

Amber, how did you get into the design world?

Amber: Well, I would say that my story is probably more emotionally driven than logically. When I started architecture school it was 2009, so it was a really bad time for the economy. Some might say I was a little crazy. “Why would you start a five-year program in architecture when the economy is so crummy?” But it was something that I kind of always knew I wanted to do, you know, from maybe from twelve years old, was to be in the design field—whether landscape architecture or interior design or architecture. But I ended up going with architecture, and now I’m marrying a landscape architect, so it totally surrounds me.

But I guess similar to Ann, I did find a sort of love and focus on historic preservation and preservation when I was in school. I actually minored in historic preservation and took opportunities when I could to study adaptive reuse—it wasn’t something that was really common in my program where I went to school in Philadelphia. I think I was one of the only ones in the program who was taking those courses, and when we did our thesis projects in our fifth year and we had a little bit of freedom to choose what we wanted to do, I actually selected a historic armory building in Philadelphia to do my project around so I could focus on a re-use project.

But, yeah. It’s just sort of a bunch of coincidence and emotionally driven as I said, a lot less logical and technological than maybe Ann’s experience. But I think growing up in New England and being in New England—whether it’s in New York or Philadelphia or Boston, where we are now—we’re just surrounded by a lot of beautiful buildings and places that maybe aren’t fully realized to their potential. And some people just look at that a little bit differently.

Amber, are your parents in design?

Amber: No, no, they’re not. They’re not in the design world at all but they did encourage all of their children to kind of follow their hopes and dreams. So my younger brother ended up being an engineer and my older sister ended up in more of a lab setting and I was somewhere sort of in-between.

Can you tell us more about adaptive reuse and restoration? What does that really entail?

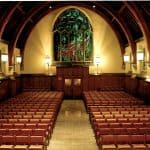

Amber: To give you the technical response, there are different definitions of those terms that are spelled out clearly in The Secretary of the Interior’s Standards. The four different ones are preservation, restoration, rehabilitation, and reconstruction. They all have different goals. The work is primarily in preservation and rehabilitation, which is like adaptive reuse. So typically, with a project or historic building that we work on, the program of that building is changing. What might have been an old bank building is becoming a library, or it might have been an old chapel and it’s becoming an auditorium. It’s not all about preserving it or bringing it back to what it once was, or re-creating something inauthentic. It’s giving the space a sort of new life and a new purpose. That’s where thinking creatively becomes really important.

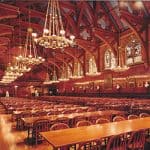

At Springfield Technical Institute, I don’t know If you’re familiar with that project? It’s a huge, long armory building that they turned into a facility for their campus. It’s a really amazing transformation of a building that was kind of a head-scratcher about how we can use something like this again. And then even the University of Chicago, that project that we did at Saieh Hall, that was formerly a seminary building actually. So, you know, even the college campus buildings aren’t always being renovated to the same sort of program that they were previously. Like Yale? The Hall of Graduate Studies is now The Center for Humanities. Even small changes like that require a lot of rethinking for the architecture.

Ann, where did you grow up?

Ann: New York City, in Midtown.

How did you choose Wellesley for college?

Ann: I was coming from a girl’s high school and was looking at Wellesley and women’s colleges. I never looked at any co-education colleges. Wellesley was a very nice option, and it’s a great college. So, there you go. I was at Wellesley when I met Fred Eustis. I was dating his roommate. I knew Fred, I knew his parents. So I knew when Bill started this chair company (Eustis Chair). He was into planes and everything, he was kind of a serial entrepreneur.

Amber: Was he was a mechanical engineer?

Ann: I think so. And he was always changing what he was interested in. And so one year he decided to buy this chair company or start it, I don’t know what it was, and then the big deal was they’d have these pictures of young Fred leaning back on the chair and not breaking it.

Amber: The Eustis Joint!

Ann: And I’m interested in that stuff, so I was like, “Wow, Fred Eustis is modeling this chair, I wonder what this is all about!” And then they were working at Harvard, and they made a lot of chairs for Harvard. The design range that they’ve gotten into is much broader now and very good, and I think it’s the durability that’s also very appealing.

Let me just say something about Eustis Chair… I’m a big durability advocate. I think that there’s a timelessness about the designs as well. I think they do extremely well for very contemporary interiors where you just want something that’s a little bit more rooted, and then you’re doing other contemporary things. And, you know, they’re just very well-made and people have very positive reactions to them. For comfort—they’re movable, they can pick them up and, for the kind of work we do which is always about collaboration and people being able to reshape their environments, that kind of a chair system is always appreciated.

Amber: Working with Eustis on the Yale project—I think absolutely durability was one of the focuses. It’s really important to the client (and a lot of institutional clients) that we’re doing fifty-plus year projects to find furniture you don’t have to change every five years. In addition to durability, sustainability is really important. Sustainability is not just about environmentally responsible materials, but the fact that the object is going to last a long time and you’re not replacing it.

I think another of the other great things about working with Eustis Chair is that we’re working with solid wood. Wood is really not as common of a material for chairs as you would think. There’s a lot of metal furniture options, there’s a lot of veneers, and it’s just not the same sort of quality that it would have been twenty or twenty-five years ago. Wood is a material we use in a lot of our projects. The ability to match a custom stain and a custom finish to our architecture (which is something we’ve been able to do successfully on both the Yale project and the Harvard project working with you guys) hat’s been really, really great! We appreciate the ability to customize wood chairs, such as adding upholstered seats that use the same fabric that we’re using elsewhere in the building. We end up with a chair that is beautiful on its own, but also matches and compliments the surrounding interior design work that we’ve done so it looks like it really belongs in the space.

I think one thing that we really appreciated was the ability to try out and test the chairs. I know we had a couple of meetings where Eustis Chair actually sent big boxes with a few different chairs to test out. The client appreciated the ability to line the chairs up in a row and have everyone do the sit test. That was really important because a lot of people are going to be spending hours sitting in these chairs. They’ve got to be comfortable. They’ve got to decide if they want arms or not., upholstered seat or not. I think that really sealed the deal for us on that project.

Selecting everything custom down to the glides was so important. We ended up with the heavy-duty mission steel glide. We selected it because it is so durable, but it’s also appropriate for carpeted floors and hard floors in most cases. This allowed a lot of flexibility, and the ability to move chairs around the room like Ann was saying. We can transform the space and not worry about drag and heavy chairs going across our newly stained wood floors and all of that. The whole chair selection process from beginning to end was a reason why we would select a company like Eustis versus picking something from a catalog.